The story of the battles that shaped Italy’s history: the three Wars of Independence and the role played by Lake Maggiore, Lake Como, and Lake Garda in decisive moments

There are some places where history seems to hang suspended in time. The three great lakes of Northern Italy — Maggiore, Como, and Garda — are perfect examples: silent mirrors that witnessed the battles, dreams, and sacrifices behind the unification of Italy, with their waters scarcely rippling. Their shores, today cherished for their peace and beauty, were once frontiers of blood and hope. It was there that the Risorgimento too shape, with its men in red shirts and its burning ideals, and it was to there that war returned in 1915, closing a circle that had been opened decades earlier. That thread of memory reaches us today, and is renewed every year on 4 November, National Unity and Armed Forces Day. This year too, at the Altar of the Fatherland in Rome, President Sergio Mattarella, accompanied by Minister of Defence Guido Crosetto, laid a laurel wreath on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, inspecting the troops lined up in Piazza Venezia.

THE FIRST TWO CONFLICTS

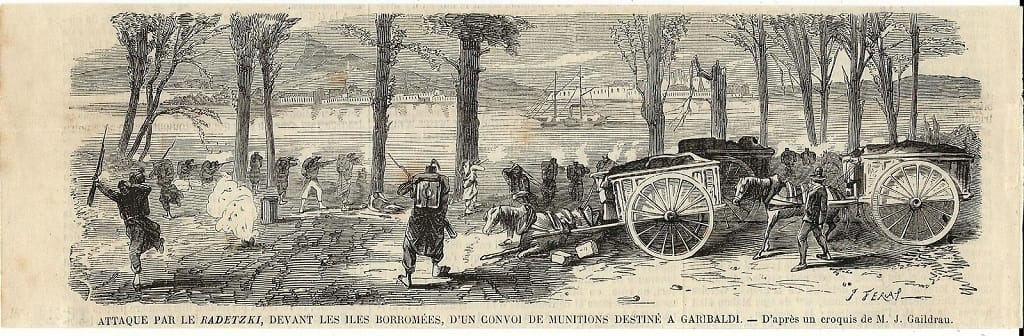

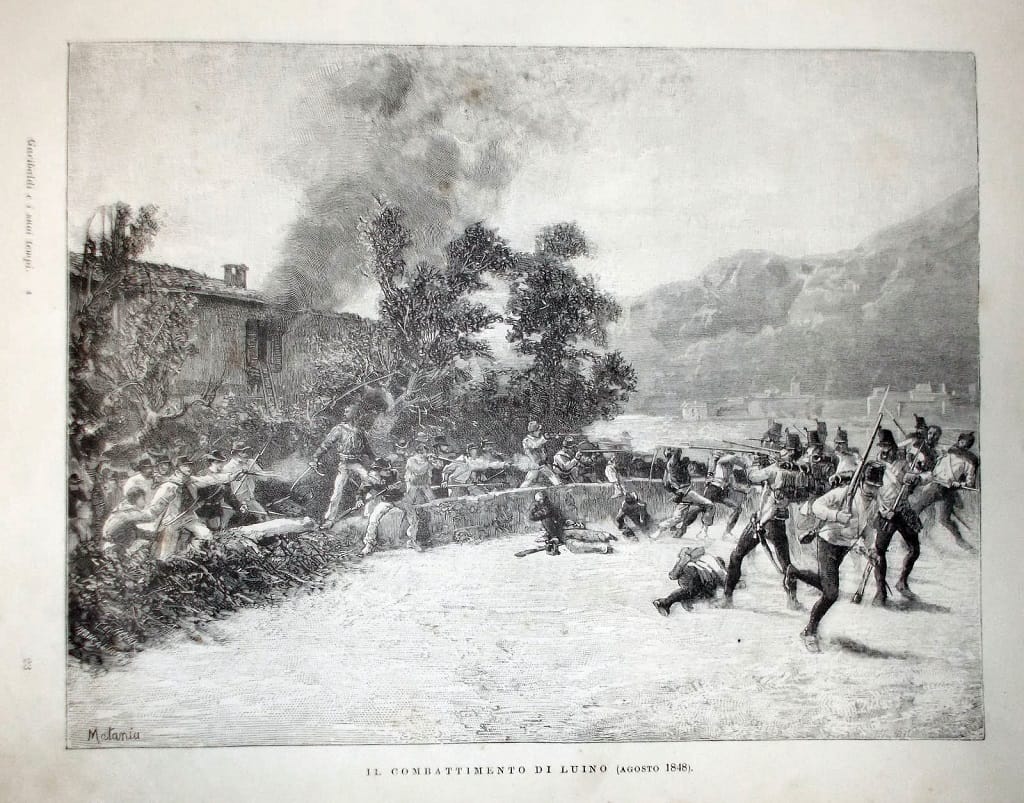

In the summer of 1848, the wind of change also blew strongly over Lake Maggiore. From Luino, a small port framed by calm waters and austere mountains, a spark that would ignite the future flared. On 15 August, Giuseppe Garibaldi landed with his volunteers, a few men, poorly armed, but full of enthusiasm, to challenge the Austrian army. The Battle of Luino was short, yet steeped in courage. The houses were shrouded in smoke, and the sound of the bells mingled with gunfire. Garibaldi was forced to retreat toward Switzerland, but that defeat turned into a legend: Luino became the symbol of a moral rebellion, the first act of a story that would find its fulfilment years later.

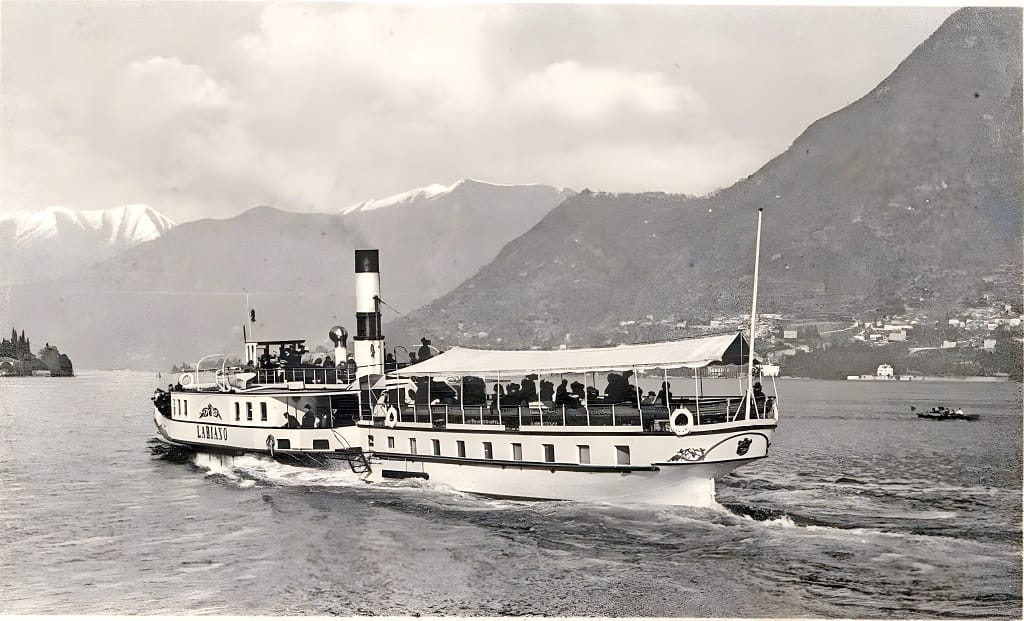

In March 1848, when the flame of the First War of Independence was ignited in Lombardy, Lake Como too became, unwillingly, the stage for tensions and hopes. The Austrian command in Como requisitioned two of the most modern vessels, the Veloce and the Lariano, leaving only the small Falco in service to maintain civil transport links. And on 27 October of that year, it was the Veloce that became the key figure in an episode still remembered on the lake. An Austrian military detachment departed from the vessel for Argegno, tasked with suppressing the Val d’Intelvi uprising led by the patriot Andrea Brenta. The mission ended in the worst possible way: the rebels resisted fiercely, and the defeated garrison had to hastily re-embark on the Veloce and return to Como, leaving behind the smoke of gunfire and the reverberations of their failure. When calm returned to the waters, life on the lake resumed its slow rhythm. At that time, steamer service began to intrigue travellers and holidaymakers: for the first time, the lake was not just a frontier or a battleground, but a gateway to discovery and marvel.

The Lariana company, sensing the potential of this new world in motion, decided to expand its fleet. In 1857, it launched the elegant and powerful steamer Unione, and two years later the Forza, which cut through the waters with thick, steady smoke, a symbol of progress that seemed unstoppable.

In 1859, when the Second War of Independence reignited the Italian dream, it was Laveno’s turn to experience its moment of glory and pain. The Piedmontese troops and Lombard volunteers attempted to wrest the town from the Austrians. Cannon fire thundered across the lake, smoke filled the streets, and the small village resisted with pride, paying a heavy price for its defiance. As the flames subsided, silence settled over the ruins, but in the hearts and minds of the people, the certainty grew that Italy was no longer just a dream.

A few weeks later, fate also came knocking on the shores of Lake Como. It was May 1859. While the Piedmontese and the French fought in the Mantua area, Garibaldi led the Cacciatori delle Alpi (Hunters of the Alps) toward the city of Como. The objective was clear: to liberate Como, drive out the Austrians, and unite Lombardy with the cause of Italy. The decisive battle took place on the high ground of San Fermo, just above the city. The narrow streets and flowering meadows suddenly became a battlefield. Garibaldi, with his red jacket and steely gaze, led his men in a bold attack. The imperial troops, surprised and demoralised, retreated. When the bells of Como began to ring in celebration, the city was free. On 27 May, 1859, Como welcomed the Redshirts as heroes. The streets were filled with tricolour flags.

Alpini and hydroplanes, icons of the Great War

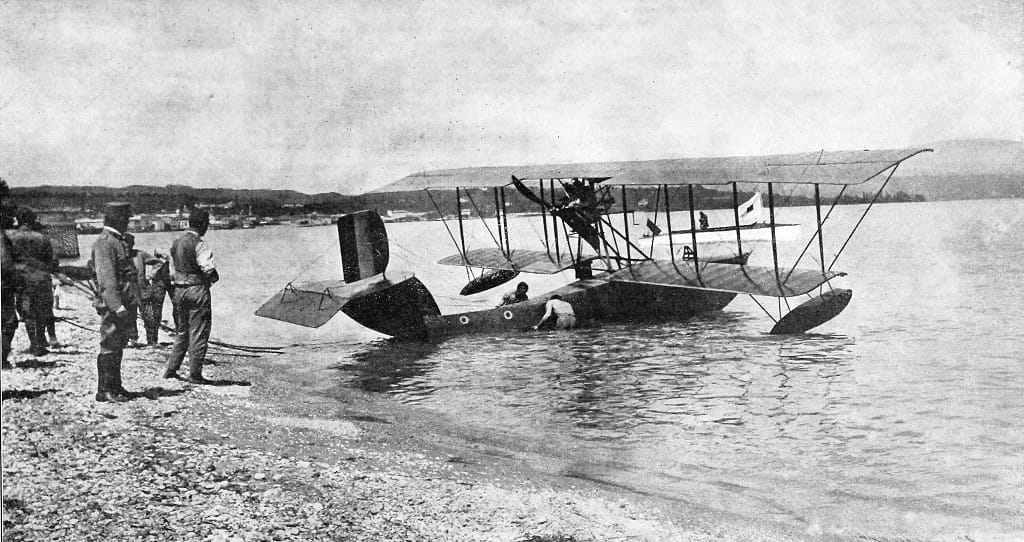

The 4 November celebrations are linked to the anniversary of the armistice that marked the end of World War I for Italy. A conflict that was significant for the territories around Lake Garda due to the Hydroplane Squadron of the Royal Italian Army. The Alpinis’ work in counterintelligence and reconnaissance proved invaluable.

Remembering the battles in symbolic locations

The 4 November ceremonies on the lakes take on an almost sacred quality In Luino, the procession follows the very streets where the battle once raged; in Como, laurel wreaths are laid beneath façades that still bear the scars of the clashes; and in Desenzano and Riva del Garda, the raising of the flag is a ritual.

GARDA AND THE THIRD WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

Lake Garda was the last one to speak the language of war. In 1866, the nation – now the Kingdom of Italy under Victor Emmanuel II – joined the Third War of Independence to liberate Veneto and Trento from Austrian rule. The mountains around Lake Garda thundered under the cannon fire. Garibaldi’s flotillas, driven by the wind, cut through the waters between Desenzano and Riva, while hospitals and command posts were set up in the towns along the western shore. At Custoza, fate was unkind to the Italian army, but further north, at Bezzecca, Garibaldi claimed one of his most brilliant victories.

When the order to retreat arrived, he replied with a single word that became legendary: “I obey.” That response reflected the understanding that Italy, through contradictions and sacrifices, was at last fulfilling its destiny. When the war ended and Veneto was annexed, the shores of Lake Garda became a symbol of unity.